Although my playthrough of Phantasy Star II sputtered to an end well before that game’s completion, my appetite for an older JRPG hadn’t been satiated. There was no shortage of such game on the Sega Genesis Classics compilation I was playing, and with most of them still new to me, I decided to stick with it for the time being. Continuing on with the next entry in the Phantasy Star series – Phantasy Star III: Generations of Doom – was an option, but I went ahead and placed it on my backlog. Instead, having learned that Phantasy Star II was the first JRPG released on the Genesis, I thought I’d follow it up with the next chronologically released JRPG (available on this compilation). That game, which debuted half a year later, was Sword of Vermilion.

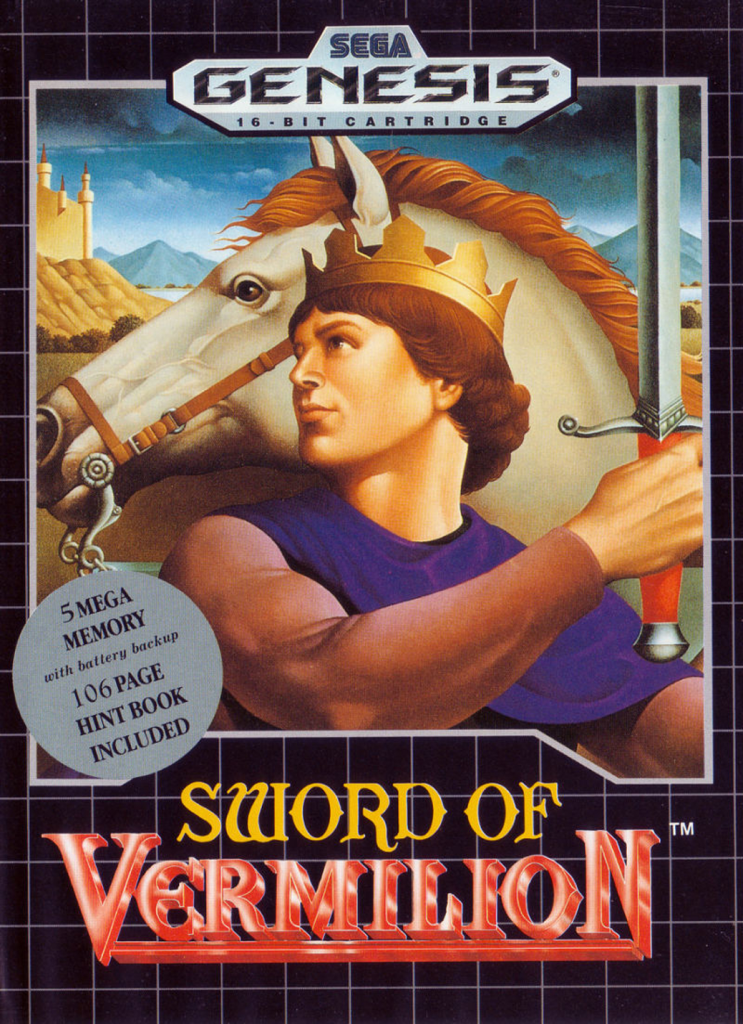

Published by Sega, first in Japan in December 1989 (as Vermilion) and then in North America during January 1991, Sword of Vermilion firmly belongs within the action-RPG subgenre, alongside games like Ys: The Vanished Omens or Zelda II: The Adventure of Link. I did not recruit and battle alongside like-minded allies as I journeyed through the realm of Vermilion. Though my avatar received much assistance, he was a solitary knight. When enemies were encountered the gameplay did transition to a battle scene, but instead of selecting actions through a menu and watching his and those of his foes play out in turns, I directly controlled the hero. In these single screen battles I hammered the attack button to slash the hero’s sword, and occasionally mixed things up by casting magic spells.

Sword of Vermilion was developed by Sega R&D #8, the internal development group formerly known as Studio 128, and soon after this game’s release, rechristened Sega AM2. This was the first time they had developed a game exclusively for a home console. Up until this point their output consisted solely of games intended for arcades, and predominantly taikan games at that, so-called “experience” games where the arcade cabinet was built to resemble the cockpit of a jet, or a motorcycle. We’re talking Space Harrier, OutRun, After Burner and more, basically the early years of a Yu Suzuki greatest hits compilation (he received credit here, but only in a special thanks capacity). Needless to say, this game was a far cry from what they’d made up until that point.

Set in a fantasy world of swords and sorcery, Sword of Vermilion began with a rather conventional setup and unfolded in a predictable manner. The player’s avatar was the sole heir of the good King Erik of Excalabria, who eighteen years prior had been murdered by the evil King Tsarkon of Cartahena. Foreseeing his death, King Erik entrusted his infant son to the most loyal knight in the land, who fled and raised him as his own, away from Tsarkon’s clutches. When this knight, Blade, dies the player character learns of his true lineage, and of his destiny to collect the eight Rings of Good and banish Tsarkon from Vermilion. From then on, I traveled the land in service of this objective.

The game followed a straightforward town-dungeon-town formula, with little chaff. There really weren’t any additional, unnecessary dungeons or overworld paths to explore. It was just go here, do this. Upon arriving in a new town, I’d speak with the half-dozen or so locals who would fill me in on current events, and hone my general objective to something more immediate, like “retrieve this item from the nearby dungeon.” I’d satisfy the local folks’ request, who in turn would provide me with direction for the next thing I should be doing. Crucially, they often provided overworld maps, too.

When navigating the overworld or spelunking through dungeons, the screen was divided into a few sections. Nearly half was the perspective of my avatar, a first-person viewpoint of his surroundings, or more accurately that which was directly ahead of him. The other major portion of the screen housed a map of the area, assuming I had one. Otherwise, it was a largely blank square wherein the silhouette of my avatar moved without context. Since I almost always received a map before heading off for the next town, most overworld travel wasn’t blind. In dungeons though, I had to find a map for each floor. They weren’t essential, but I was compelled to explore every nook and cranny, so you bet I eventually came upon each and every one.

As I explored dungeons or traveled across the overworld, the hero was confronted by hordes of enemies. Random battles occurred with great frequency – sometimes I’d exit a battle scene only to take one step and be whisked off to another – and presented a different perspective. Taking place in single screen settings, viewed from a quasi top-down/side angle, I hacked and slashed my way through upwards of ten foes. There were about a dozen enemy types, and I came across numerous palette swaps across my twenty hour adventure. I never had to fight more than one type at a time and each had their own characteristics. Over time I learned which ones required me to more offensive or defensive, and which ones I should just avoid altogether (poisonous enemies, just avoid poisonous enemies).

Yet another gameplay mode and perspective was implemented with boss battles. These dozen or so encounters took place within the confines of a single screen like the regular battles, but pivoted the action to that of a side scroller. In doing so much larger, more detailed sprites were used and the bosses were way more menacing and impressive than anything else the hero faced. Battling these creatures required a more methodical approach to combat. Instead of hacking and slashing fairly mindlessly, I’d have to watch the boss’ movement to spot an opening, move in to strike, back out before sustaining too much damage, and repeat a couple more times. They could take me out with just a few hits, so I relied upon this compilation’s rewind feature while learning their patterns of movement.

With Sword of Vermilion, Sega R&D #8 blended a variety of RPG styles and perspectives into a successful amalgamation of what was in vogue in the late 1980s/early 1990s. After a couple hours, I’d been introduced to the game’s simple progression cycle and from then on, I may as well have been completing a formulaic paint-by-numbers puzzle. That’s not to say the game wasn’t challenging, or that I didn’t find satisfaction in exploring a dungeon, but it was, let’s say, a non-exciting experience for most of its twenty hours. I did see it through to completion though, so it obviously wasn’t totally unenjoyable. And there’s the back of the box quote: “not totally unenjoyable.”